I’ve always had somewhat mixed feelings about Alice in Wonderland, which might be considered odd given that I own at least seven different editions, including the Norton Critical Edition (1992; all quotations to follow are taken from this text). I love Lewis Carroll’s language play and the sheer absurdism/surrealism of the narrative, but I feel it’s a cheat to sum up Alice’s experiences as just vivid dreams (perhaps it’s earlier pop cultural scars caused by Pam’s waking up to find in the shower Bobby, wet but no longer dead). My mixed feelings could also stem from the fact that I didn’t read Alice until fifteen years ago, when I was in my mid-twenties and perhaps too old for a first reading (I’d seen the Disney film, of course, and I had read extensively about the novel). I enjoyed it, but I didn’t quite feel like I connected to it, much the same way I felt after reading Catcher in the Rye. But that’s another story. Warning: Spoilers to follow.

I’ve always had somewhat mixed feelings about Alice in Wonderland, which might be considered odd given that I own at least seven different editions, including the Norton Critical Edition (1992; all quotations to follow are taken from this text). I love Lewis Carroll’s language play and the sheer absurdism/surrealism of the narrative, but I feel it’s a cheat to sum up Alice’s experiences as just vivid dreams (perhaps it’s earlier pop cultural scars caused by Pam’s waking up to find in the shower Bobby, wet but no longer dead). My mixed feelings could also stem from the fact that I didn’t read Alice until fifteen years ago, when I was in my mid-twenties and perhaps too old for a first reading (I’d seen the Disney film, of course, and I had read extensively about the novel). I enjoyed it, but I didn’t quite feel like I connected to it, much the same way I felt after reading Catcher in the Rye. But that’s another story. Warning: Spoilers to follow.

A few years ago I was struck by a story idea, which literally woke me up one morning: a grown-up steampunkish Alice as a Wonderland bounty hunter. I knew I needed to reread Alice and pay more attention as a writer instead of a reader in order to create my “sequel,” but as I delved back into Carroll’s novels I debated on which elements I should focus. Obviously, I could examine Carroll’s most prominent writerly convention—language play, especially his fondness for puns—but since I don’t use a lot of puns myself, that kind of an examination wouldn’t help me. Instead, what I decided to study as I reread were those particular elements of the Alice books that I might incorporate into my own story: Alice’s personality and the role of her sister.

Obviously, I wanted to base my adult-Alice on Carroll’s seven-year-old Alice, but despite the precociousness of Carroll’s Alice, I wasn’t sure I’d find a lot of useful characteristics to work into my own adult characterization. The child-Alice is adventurous, curious, courageous, rather stubborn, but still kind (in a rather practical, often brusque way), and that she has a “favourite little toss of the head” (129) and that “she was always rather fond of scolding herself” (192), all of which is helpful but didn’t help me find a way completely into my character. But several statements by or about the child-Alice, however, did get my brain whirring. First, a line from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: “this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people” (12), and then this passage from Through the Looking-Glass:

[Alice] had quite a long argument with her sister only the day before—all because Alice had begun with “Let’s pretend we’re kings and queens,” and her sister, who liked being very exact, had argued that they couldn’t, because there were only two of them, and Alice had been reduced at last to say “Well, you can be one of them, then, and I’ll be all the rest.” (110)

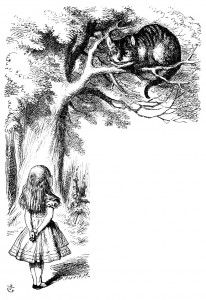

Not long after that passage Alice momentarily forgets her name (135-137), until reminded by a Fawn, who at first is friendly to Alice and then frightened of her; after the Fawn bounds off into the forest, Alice says, “However, I know my name now, … that’s some comfort. Alice—Alice—I wo’n’t forget it again” (137). Further along, after Alice has met the vexing Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the latter tells Alice that the Red King is dreaming her and asks, “And if he left off dreaming about you, where do you suppose you’d be? … You’d be nowhere. Why, you’re only a sort of thing in his dream!” (145). To which Tweedledum adds, “If that there King was to wake … you’d go out—bang!—just like a candle!” (145). My original conception of the adult-Alice was that she would track down and trap creatures who had escaped Wonderland and the Looking-Glass world, that her experiences as Carroll recorded them weren’t experienced in a dream but in fact in another world. But the above passages made me wonder if it wouldn’t be more interesting to make adult-Alice more ambiguous: is she chasing down real creatures or figments of her imagination? Carroll tells us that Alice often pretends to be two or multiple people, that she loses her name (and thus her identity), that her existence might stem only from the Red King’s dreaming her—all bits that support the idea of an adult-Alice with some kind of personality disorder, thus offering me the opportunity to layer in some ambiguity into my story.

Not long after that passage Alice momentarily forgets her name (135-137), until reminded by a Fawn, who at first is friendly to Alice and then frightened of her; after the Fawn bounds off into the forest, Alice says, “However, I know my name now, … that’s some comfort. Alice—Alice—I wo’n’t forget it again” (137). Further along, after Alice has met the vexing Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the latter tells Alice that the Red King is dreaming her and asks, “And if he left off dreaming about you, where do you suppose you’d be? … You’d be nowhere. Why, you’re only a sort of thing in his dream!” (145). To which Tweedledum adds, “If that there King was to wake … you’d go out—bang!—just like a candle!” (145). My original conception of the adult-Alice was that she would track down and trap creatures who had escaped Wonderland and the Looking-Glass world, that her experiences as Carroll recorded them weren’t experienced in a dream but in fact in another world. But the above passages made me wonder if it wouldn’t be more interesting to make adult-Alice more ambiguous: is she chasing down real creatures or figments of her imagination? Carroll tells us that Alice often pretends to be two or multiple people, that she loses her name (and thus her identity), that her existence might stem only from the Red King’s dreaming her—all bits that support the idea of an adult-Alice with some kind of personality disorder, thus offering me the opportunity to layer in some ambiguity into my story.

After rereading the novels, I had a solid direction in which to take my adult-Alice and the story as a whole, but the first thing that struck me when I started rereading Alice is the presence of Alice’s older sister, whom I had quite forgotten from my first reading but realized I had to include her in my “sequel.” Of course, the older sister serves as the frame for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: at the beginning of Alice, the sister is the one reading the book with “no pictures of conversations in it” (7) while Alice grows quite bored and thus escapes to Wonderland. At the end, when Alice wakes up with her head in her sister’s lap, Alice tells her sister the adventures that have come in between:

And she told her sister as well as she could remember them, all these strange Adventures of hers that you have just been reading about; and, when she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said “It was a curious dream, dear, certainly; but now run in to your tea: it’s getting late.” (98)

Carroll also tells us at the middle and at the end of Through the Looking-Glass that Alice tells her Looking-Glass adventures to her sister: “‘But it certainly was funny,’ (Alice said afterwards, when she was telling her sister the history of all this,)…” (139) and “when [Alice] was explaining the thing afterwards to her sister” (207).

(A side-note: To address my comment in the first paragraph, the endings of these novels seem a cheat to me in that they diminish the beauty and savagery of Wonderland and its effect on an extremely precocious seven-year-old. The Adventures weren’t real—they were dreamed—and therefore brushed off as only a play of the imagination rather than an affecting experience. Often, some authors diminish the power of the fantastic by presenting it as a dream from which one can wake and be free of it; The Wizard of Oz does something similar with its frame narrative. I do not approve.)

The sister serves two purposes at the end of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (and, one might assume, off-stage at the end of Through the Looking-Glass): first, her presence marks Alice’s return to the “familiar” world; second, and more importantly, she is the listener-recipient of Alice’s Wonderland’s stories, which makes those stories “real” (in the sense of “real” that some people use: “It wasn’t real until I told you about it”). Indeed, after Alice has run in to tea, Carroll focuses on the sister for the last page of the novel and how the sister falls asleep and basically dreams Alice’s adventures as vividly as Alice did, except that the sister dreams Alice’s adventures as we have read them: the sister observes but does not (cannot?) participate. Was Carroll’s purpose with the sister’s dream to reinforce the idea that Alice’s adventures were only a dream? To persuade us of the sheer vividness of Alice’s dreaming power in that the retelling of it so acutely and precisely influenced the sister’s dreaming in turn? Carroll uses the sister in the last paragraph of Adventures to convey his intent to the reader:

The sister serves two purposes at the end of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (and, one might assume, off-stage at the end of Through the Looking-Glass): first, her presence marks Alice’s return to the “familiar” world; second, and more importantly, she is the listener-recipient of Alice’s Wonderland’s stories, which makes those stories “real” (in the sense of “real” that some people use: “It wasn’t real until I told you about it”). Indeed, after Alice has run in to tea, Carroll focuses on the sister for the last page of the novel and how the sister falls asleep and basically dreams Alice’s adventures as vividly as Alice did, except that the sister dreams Alice’s adventures as we have read them: the sister observes but does not (cannot?) participate. Was Carroll’s purpose with the sister’s dream to reinforce the idea that Alice’s adventures were only a dream? To persuade us of the sheer vividness of Alice’s dreaming power in that the retelling of it so acutely and precisely influenced the sister’s dreaming in turn? Carroll uses the sister in the last paragraph of Adventures to convey his intent to the reader:

Lastly, [the sister] pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood; and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago; and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days. (99)

The sister’s vision of the future-Alice seems sentimental from a 21st-century perspective, that this singular dream would influence and direct the life of future-Alice in absolutely positive ways. But my re-discovered presence of the sister—even in the ways I find less appealing—inspired me. For my steampunk-ish version, the sister in Carroll’s novels became a steam-powered automaton (or at least one run on clockwork; I had this image of a female-shape with a removable chest to allow viewing of the automaton’s inner workings), which Alice referred to as “sister” and to which Alice reported her adventures. The sister-automaton also serves as a confidante to the adult-Alice, and, like Carroll’s sister, observes rather than participates. I’m not entirely confident, however, that the sister-automaton works effectively enough within the story, and, like gaslight, she may need to fade away if I can’t make her more important to the plot.

Writing “Under the Looking-Glass” was a trickier use of source material than I’m accustomed to, as I wasn’t as familiar with Carroll’s novels as I have been with other source material (like the Persephone myth or the Baba Yaga and Mother Hulda fairy tales) I’ve used as story inspirations. However, I learned a lot from the process (and I especially enjoyed working again in late-19th-century London) and will perhaps (hopefully?) write additional sequels to my “sequel.”