Slipstream isn’t a genre I’d been very familiar with prior to reading Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology, edited by James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel; I’d heard of slipstream, read many writers who are apparently engaged in it (though to say writers are “engaged in” writing slipstream is perhaps a bit misleading, given that the label seems more an external application than an authorial intention), but I hadn’t really pursued an analysis of it as a genre. Warning: Spoilers to follow.

Slipstream isn’t a genre I’d been very familiar with prior to reading Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology, edited by James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel; I’d heard of slipstream, read many writers who are apparently engaged in it (though to say writers are “engaged in” writing slipstream is perhaps a bit misleading, given that the label seems more an external application than an authorial intention), but I hadn’t really pursued an analysis of it as a genre. Warning: Spoilers to follow.

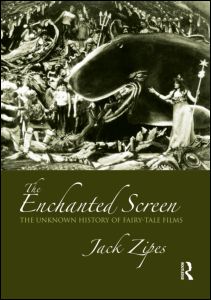

The introduction to Feeling Very Strange gave me a lot to think about, and one idea that particularly stands out is that “Nobody calls mainstream writers ‘mainstream’ except for those of us in the ghetto of the fantastic” (viii). That certainly raises an age-old question for me about how writers classify themselves; non-genre writers are just writers and “acceptable,” whereas genre writers are of a different breed altogether. Michael Chabon, obviously, is a writer who’s embraced genre, though he probably isn’t considered a genre writer by the “mainstream.” Aimee Bender’s work, from what I’ve read, tends to border fantasy of the magic realist ilk, although I’d argue that “The Healer” falls more heavily into genre than slipstream. I wonder if she’s not pegged as more of a genre writer because she has a tendency towards postmodernism and “odd things” seem to be accepted in postmodernism where they aren’t in mainstream literature. Relatedly, in an interview in the October 2008 Locus, Ursula K. Le Guin—certainly someone categorized as a genre writer though she writes just about every kind of thing—had some interesting thoughts about this divide, which I’d like to share (apologies for the length):

I think both science fiction and fantasy are now becoming part of the mainstream. I wanted them to be respected as part of the mainstream—I didn’t want genre snobbishness to prevail… I think it’s improving the mainstream, but I’m not sure it’s improving science fiction.

I wish I was as good-natured as Michael Chabon about writers who write science fiction but don’t allow it to be called that (or their publishers don’t), like Cormac McCarthy. Geez! The cross country trip through the ruins has been done, and in better English than he writes. But he gets all this respect and special treatment for it, meaning that snobbishness still prevails. I get really cross about people waltzing off with literary prizes for writing second-rate science fiction. (So there!) And I long to warn the people coming into SF from elsewhere, be quite sure you’re not reinventing the wheel for the 50th time. That was my main objection to Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake. Whereas The Handmaid’s Tale was solid, inventive science fiction.

I wish Le Guin had elaborated more on how the growing mainstream acceptance of genre is improving mainstream but perhaps negatively affecting genre. Certainly, more and more “mainstream” writers are edging into genre one way or another—sometimes, as Le Guin points out, covering ground already well explored—and a fair number of genre writers seem to be moving into what would be considered mainstream territory (Karen Joy Fowler and Elizabeth Hand spring to mind). Of course, one could—should?—argue that good writing transcends genre, but too often it doesn’t, at least in terms of literary respect, as Le Guin points out.

All of which leads me back to Feeling Very Strange and trying to sort out how these authors fit into genre (or don’t). Interestingly enough, I was familiar with almost every writer in the anthology prior to reading it, in some way or another, but I hadn’t considered their writing in the context of “slipstream” but often more in the sense of postmodernism or magic realism (in my broad definition of the latter, as I’ve mentioned before). So I undertook reading Feeling Very Strange to look, first, at how the writers use postmodernist techniques in genre writing and, second, at how they made me feel “strange” after reading their stories.

I’ll begin with Kelly Link’s story, “The Specialist’s Hat.” My inclination in trying to define Kelly’s work has been to use the term “postmodernist fantasy”; indeed, when I taught 20th Century Fantasy & Film, a special topic course, a few years back, I classified Link’s collection, Stranger Things Happen, as postmodernism, not having the sense to label it “slipstream” instead. (Of course, I should have hesitated even to use the term “fantasy,” as I’ve read somewhere that Kelly labels herself a science fiction writer.) One of the many things I like about Kelly’s work is that she creates for me in every piece of that sense of something “strange” going on, that little tonal something that shifts a story, presumably, into slipstream. “The Specialist’s Hat” gives me that feeling, although here the feeling is more dread than strangeness, although I suppose they can be closely related. Part of that feeling stems from my initial recognition that the babysitter is Rash’s daughter, and even then it’s a vague feeling; it begins when “…the babysitter showed up precisely at seven o’clock. The babysitter, whose name neither twin quite caught, wears a blue cotton dress with short floaty sleeves. Both Samantha and Claire think she is pretty in an old-fashioned sort of way” (44). I don’t know why I begin to suspect the babysitter at this point; is it because she doesn’t have a name and Rash’s daughter is never named? Is it because her prettiness is “old-fashioned”? The more careful reader probably has caught the hints Kelly drops on the first page of the story, when the babysitter introduces us to the Specialist as a kind of bogeyman and tells the twins she used to live in the house. Once I recognize the real strangeness in the story, that feeling grows stronger over the rest of the narrative, with the chimney and the hat and the mysterious woman in the woods. The weird mixing culminates at the end of the story by seeming to blue the past Rash/daughter narrative and the present dad/Samantha & Claire narrative, when the twins’ father is seen by them suddenly as the Specialist, a danger they have to escape by hiding inside the chimney (and, I think, dying there), which only serves to heighten the dread/strangeness—and the end of the story doesn’t abate that dread.

The postmodernism in “The Specialist’s Hat” comes in several shapes. One shape for me is the mix of vagueness and specificity that generally permeates Kelly’s work. Most characters in the story aren’t named, or even described, and even the plot feels vague and undefined (postmodern in and of itself). But there is a sharp contrast with certain moments of specificity, as in the descriptions of the house and its contents, or when we’re told that “[Their mother] has been dead for exactly 282 days” (41) and “Without counting, she suddenly knows that there are exactly fifty-two teeth on the hat” (49). The lack of a clear ending also suggests postmodernism.

Another story that caught my attention was Jeffrey Ford’s “Bright Morning.” The beginning was enticing (I teach Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” regularly), and I was engaged by the idea of a writer writing about writing, as well as his connection to a fictional Kafka story (though one I would have enjoyed reading). For the longest time in the story, I didn’t see why one would consider it slipstream; then I reached the bottom of page 170, when the description of the narrator’s writing career and success sounded very much like the author Jeffrey Ford’s writing career and success. I thought the “feeling strange” therefore came from this mixing of autobiography and the fantastic (the stories circulating “Bright Morning” seemed too coincidental, too perfectly fitted together to be anything other than fantastic). But then “Jeffrey Ford” walks into the story on page 178, and I’m blown out by it, perhaps because I hadn’t expected it, perhaps because it’s just a clever trick. And then I did indeed feel very strange, trying to wrap my head around what I thought I understood about the story paired with understanding the now-obvious metafictional technique of the author himself appearing in a first-person narration. What speaks to Ford’s strength as a writer is that the sudden metafictional shift doesn’t feel contrived or gimmicky, but it certainly made me re-evaluate the “reality” of the story.

After reading and enjoying Feeling Very Strange, what I come away with, finally, is no clearer understanding of how to categorize my own writing (in terms of marketing my work). Most of what I write I think fits Farah Mendlesohn’s definition of “intrusion fantasy,” described in Rhetorics of Fantasy, which is still a broad category and doesn’t exclude slipstream, of course. But I don’t think my writing quite fits into slipstream, if only because—to me, anyway—the sense of “feeling very strange” isn’t present after reading it, even though I continue to strive for that effect.

Neil Gaiman has long been a favorite writer of mine, going back to The Sandman. And, because his work is often published in limited editions, he feeds not only a reading love but also a bibliophilic one. I certainly enjoyed his last novel, The Graveyard Book (HarperCollins, 2008), and have several different editions. One aspect of that novel to me as a writer was its structure: a novel told through short stories, a form in which I’m particularly interested (this form is also called a mosaic novel, although that term is sometimes used more specifically). Some questions I’ve decided to investigate: How did Gaiman keep the structure unified? How did he interconnect the stories but give them enough substance that they might be read complete in themselves? And, on a tangentially related note, how did he handle point of view? Warning: Spoilers to follow.

Neil Gaiman has long been a favorite writer of mine, going back to The Sandman. And, because his work is often published in limited editions, he feeds not only a reading love but also a bibliophilic one. I certainly enjoyed his last novel, The Graveyard Book (HarperCollins, 2008), and have several different editions. One aspect of that novel to me as a writer was its structure: a novel told through short stories, a form in which I’m particularly interested (this form is also called a mosaic novel, although that term is sometimes used more specifically). Some questions I’ve decided to investigate: How did Gaiman keep the structure unified? How did he interconnect the stories but give them enough substance that they might be read complete in themselves? And, on a tangentially related note, how did he handle point of view? Warning: Spoilers to follow.