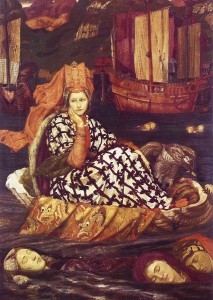

Confession: I have a deep and abiding affection for the Victorian period (no one reading this blog will be surprised to hear it, so the use of the word “confession” is just a little extra melodrama for you). Something about the restrained manners hiding a morally murky underbelly just fascinates me—all that paradox, repression, and oppression, plus the Pre-Raphaelites. What’s not to love? I have shelves of books on Victoriana, and its influence on speculative fiction delights me as a reader. But I have to say that while I’ve known and about steampunk for a long time and have read a little, mostly Paul Di Filippo’s work, I haven’t really read much in the genre because steampunk is tethered in science fiction, and I’m a fantasist who rarely dabbles in my sister genre. Warning: Spoilers to follow.

Confession: I have a deep and abiding affection for the Victorian period (no one reading this blog will be surprised to hear it, so the use of the word “confession” is just a little extra melodrama for you). Something about the restrained manners hiding a morally murky underbelly just fascinates me—all that paradox, repression, and oppression, plus the Pre-Raphaelites. What’s not to love? I have shelves of books on Victoriana, and its influence on speculative fiction delights me as a reader. But I have to say that while I’ve known and about steampunk for a long time and have read a little, mostly Paul Di Filippo’s work, I haven’t really read much in the genre because steampunk is tethered in science fiction, and I’m a fantasist who rarely dabbles in my sister genre. Warning: Spoilers to follow.

Steampunk, to offer a basic definition from the genre’s entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by John Clute and Peter Nicholls (St. Martin’s Griffin, 1995), is a term “coined in the late 1980s … to describe the modern subgenre [which began in the 1970s] whose [science fiction] events take place against a 19th-century background” (1161). According to the Encyclopedia entry, steampunk is set specifically in Victorian London, although I have found that is not exclusively the case (at the very least, the only examples the Encyclopedia offered fourteen years ago were set in Victorian London).

While Clute and Nicholls present a basic definition from which to work, Jess Nevins’ introduction to the anthology Steampunk (Tachyon, 2008. All subsequent quotations are taken from this text), edited by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, gave me some more substantive ideas to contemplate. (It’s worth noting that Steampunk collects previously published work [ranging in time from 1971-2007], some by notable authors in the subgenre; five months after Steampunk’s publication, the Nick Gevers-edited anthology of all-original steampunk work, Extraordinary Engines: The Definitive Steampunk Anthology, was published. Comparing the two might have produced some interesting thoughts about the genre, considering there seem to be “waves” or “generations” of steampunk.) Nevins says, “Steampunk, like all good punk, rebels against the system it portrays (Victorian London or something quite like it), critiquing its treatment of the underclass, its validation of the privileged at the cost of everyone else, its lack of mercy, its cutthroat capitalism” (10), a statement which resonated with me. I’d pictured steampunk—as well as related ‘punks in speculative fiction, like cyberpunk (the granddaddy of ‘punk movements in speculative fiction) and splatterpunk (a subgenre of horror fiction)—as a kind of “extreme” genre, in the way that splatterpunk is more gory and visceral than other horror. But Nevins’ summation of “all good punks” as rebellion “against the system” made me start thinking of steampunk in a different way, or at least first generation steampunk (Nevins contends that second generation steampunk has “little to nothing ‘punk’ about it” [10])—more in the way I think about the punk music scene as this brash movement that exposes hypocrisy and attempts to inject energy back into the culture. Steampunk tries to cut through the outer layer of Victorian society and get at its hidden savage heart, and this critique of the 19th century appeals to me, especially when considering Nevins’ belief that

More so that other historical periods, the 19th century, especially the Victorian era (1837-1901), is an excellent mirror for the modern period. The social, economic, and political structures of the Victorian era are essentially the same as our own, and their cultural dynamics—the way in which the culture reacts to various phenomena and stimuli—are quite similar to ours. This makes the Victorian era extremely useful for ideological stories on subjects such as feminism, imperialism, class issues, and religion, as well as for commentary on contemporary issues such as serial murderers and overseas wars. (8)

I had never considered just how well the Victorians mirror contemporary society, but it offers exciting possibilities for using steampunk to address or critique current ideas.

Moving into the stories themselves, I kept the above ideas in mind, but I also paid attention to how the authors built their steampunk worlds inside the brief life of a short story. James P. Blaylock’s “Lord Kelvin’s Machine,” a first-generation steampunk story, is constructed around an adventure of Langdon St. Ives of Victorian (or Edwardian) England. While he has written a story with a “pulpy” feel to it (in terms of its rousing and harrowing action), Blaylock is clearly relying on a Victorian-esque writing style as one means of conveying the story’s steampunk setting. The science is less important here than the science fiction plot—a madman threatens to cause volcanic eruptions that will move the earth out of its orbit into the path of an oncoming comet, and it’s up to St. Ives to stop him since the Royal Academy of Sciences isn’t convinced by the threat and have their own equally problematic solution to the comet. Not a lot of time is spent describing the anachronistic technology used in the story; indeed, there’s not a lot of technology to describe. These elements instead are background for the story, offering texture and depth rather than a focus for the reader.

For me, an even better example of steampunk—one which convincingly conveys its time period as well as its science—is “Minutes of the Last Meeting” by Stepan Chapman, which is set in 1917 Russia. At first, I was a little surprised at this story’s locale; as I mentioned earlier, I thought steampunk had to be set in Victorian England, and “Minutes of the Last Meeting” moves away from both the 19th century and the expected locale (other authors, however, move even further afield into secondary worlds that feel vaguely 19th century but are certainly not recognizable as our own). However, Chapman convincingly melds the past with science fiction. For example, the story is largely set on a train powered by a steam engine, but aboard the train “the hemophiliac tsarevich” (308) undergoes heart surgery to be conducted by nanotechnology. The secret police is actually the Imperial Intelligence Entelechy, a cybernetic computer brain with 999 vesicles (micro sentient spy cameras, often in the forms of insects). Scientists experiment with a uranium-powered missile, which at the end of the story destroys the world (not quite the ending one expected—it takes the massacre of Tsar Nicholas II and his family to an extreme conclusion). This melding of the 1917 time period with advanced technology makes for an engaging read, as does Chapman’s use of multiple viewpoints; I counted at least twelve different points of view used, and all these characters are inter-related. Maintaining that delicate balance of connecting everyone without making those connections seem labored is quite a feat.

While I’m not sure how much more steampunk (or steampunkish) stories I’ll write (I’m more of a gaslight romance man), reading Steampunk certainly gave me a lot to think about, not only in thematic terms (the critical and rebellious nature of punk) but also in constructive terms (Chapman particularly on how to incorporate science fiction seamlessly into a historical period without letting it dominate). Recently, I bought a copy of Ghosts by Gaslight: Tales of Steampunk and Supernatural Suspense, edited by Jack Dann and Nick Gevers, which I hope to read and annotate soon. Though I don’t write ghost stories per se, I am interested in haunted characters, and this genre is more in line with my sensibilities than science fiction. Since the stories of this new anthology are set in the 19th century, reading Ghosts by Gaslight should make for an interesting comparison to Steampunk.