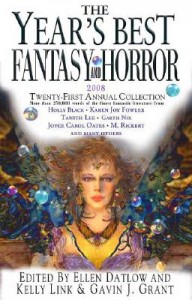

Although I’d read The Year’s Best Fantasy & Horror series (St. Martin’s, 1988-2008) since its inception, I’ve never read any one volume as deliberately as I read the 2008 edition (the 21st volume in the series and, sadly, the last). Typically I’d read the “Year in Fantasy” summation, along with the annual round-ups of comic books and films, and then I dip in and out of the collected stories, normally reading only writers I’m familiar with or stories that get my attention for one reason or another. At best, I’d say I’ve been a casual reader, and so, when I opened the 2008 edition, I felt that certainly I would learn more about the current market than I have in years past (“current,” of course, is a slippery term, considering this edition is now three years old). Warning: Spoilers to follow.

Although I’d read The Year’s Best Fantasy & Horror series (St. Martin’s, 1988-2008) since its inception, I’ve never read any one volume as deliberately as I read the 2008 edition (the 21st volume in the series and, sadly, the last). Typically I’d read the “Year in Fantasy” summation, along with the annual round-ups of comic books and films, and then I dip in and out of the collected stories, normally reading only writers I’m familiar with or stories that get my attention for one reason or another. At best, I’d say I’ve been a casual reader, and so, when I opened the 2008 edition, I felt that certainly I would learn more about the current market than I have in years past (“current,” of course, is a slippery term, considering this edition is now three years old). Warning: Spoilers to follow.

Fantasy editors Kelly Link and Gavin Grant selected nineteen out of the forty works in the anthology, and horror editor Ellen Datlow also selected four of the same pieces. Three of the fantasy selections were poems, and so I did not include them in my analysis (Catherynne M. Valente’s poem, though, is substantial enough in length that one might count it as another short story).

In their summation, Link and Grant point out that “This was another year in which many of our favorite short stories were published in original anthologies and online venues” (xvii), which makes me wonder if there are fewer periodical print venues than before (or perhaps original anthologies and online venues are strengthening in quality and quantity). What follows is a breakdown of the publication venues:

- Nine of the sixteen fantasy prose selections were published in original print anthologies. Of those nine selections, three came from The Coyote Road, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling; two came from Eclipse One; and one each from Logorrhea, Wizards, The Restless Dead, and Interfictions. Interestingly, two of those anthologies—The Coyote Road and The Restless Dead—are aimed at young adult readers.

- Three of the selections were published in exclusively online venues: Strange Horizons, Baen’s Universe (sadly, now closed), and Fantasy Magazine.

- Three selections were published in exclusively print periodicals (one in Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Circlet and two in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction).

- And, finally, one selection was published by a print periodical that has a substantial online presence (Zoetrope All-Story).

They also mention “much of the best work was published in young adult” (xvii), which is something that didn’t surprise me; I’ve been aware of the boom in YA publishing because of curriculum research (I teach a course in Adolescent Literature), and frequently writers mention that this is a “golden age” of YA publishing, not simply in terms of quantity but also, as Link and Grant say, in quality.

Looking at particulars of the selections:

- Only one story—Garth Nix’s “Sir Hereward and Mister Fitz Go to War Again”—was an immersion or secondary-world fantasy, which I found a little surprising given how popular that sub-genre is in book-length works.

- Three stories were historical fantasies: Daniel Abraham’s “The Cambist and Lord Iron: A Fairy Tale of Economics” (set in an indeterminate locale, seemingly in the 18th or 19th century; I thought the setting was England, because Lord Iron wanted his mysterious currency exchanged for pounds sterling, but I may have been over-rationalizing), M.T. Anderson’s “The Gray Boy’s Work” (set during the Revolutionary War), and Ted Chiang’s “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate” (set in historical Egypt).

- Four stories had no overtly fantastical elements, though several of them might be slipstream: “The Cambist and Lord Iron” has no fantasy at all, other than its indeterminate setting; “The Last Worders” by Karen Joy Fowler also had no fantasy, but it felt very much like a Kelly Link (Linkensian? Linkist? Linkese?) story in its strangeness; “Fragrant Goddess” by Paul Park did not have any overtly fantasy elements, although it had a slipstream feel to it and also a touch of alternate history; and “Rats” by Veronica Schanoes likewise had no overt fantasy elements (the rats could be hallucinations, after all). I might also include “Vampires in the Lemon Grove” by Karen Russell here as having no fantastical elements because although the narrator and his wife are both vampires, Russell tells the story in a very realistic style, where the vampire elements serve more as a transparent metaphor than as an integral part of the story.

- Eight stories—half of the selections—drew on fairy tales and myths in various ways, either very directly or simply in the use of tropes: “The Cambist and Lord Iron” had a fairy-tale feel to it by way of the three exchanges the Cambist must make, each increasing in peril, and the exchanges each time bring about transformations for both characters; Delia Sherman’s “The Fiddler of Bayou Teche,” Holly Black’s “A Reversal of Fortune,” and Kij Johnson’s “The Evolution of Trickster Stories Among the Dogs of North Park After the Change” are trickster tales; Elizabeth Hand’s “Winter’s Wife” and Lucy Kemnitzer’s “The Boulder” both draw on the same Icelandic huldur folk myths (the latter is also interesting because the only names given in the story are to the two sets of brothers, one folkloric, one real; every other character is identified by profession only: the archaeologist, the folklorist, etc.); “Rats” evokes fairy tales at the beginning and is a retelling of the Sleeping Beauty tales (and has one of my favorite lines from the anthology: “The house was quiet and always remained neat as a shot of bourbon” [311]); and Liz Williams’ “The Hide” alludes to Celtic myth and the land of the dead.

- Nine of the sixteen were written in first-person (one being a “we” narrator): “Vampires in the Lemon Grove”; “The Last Worders”; “The Fiddler of Bayou Teche”; “Up the Fire Road” by Eileen Gunn (which had two alternative first-person narrators and more surrealistic perspectives than you can shake a stick at); “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate”; “Rats”; “The Hide”; and “The Evolution of Trickster Stories Among the Dogs of North Park After the Change” (the “we” narrator).

If I were to make some generalizations about the market based on the particulars of the fantasy selections from The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror 2008, I’d say that the trends seem to be first-person narratives, fairy-tale- or myth-based narratives, and slipstreamish or non-overtly fantastic narratives. Those trends are good news for me, as I tend to write stories that mesh with at least two of those trends.