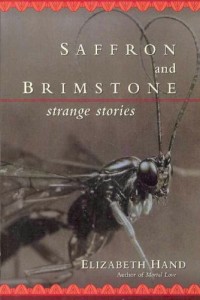

When I read, I generally read for either (a) work or (b) pleasure. I analyze so much of the reading I do for work that when I read for pleasure I try consciously not to analyze too much; I will, however, be prompted by particularly fine writing to start reading it aloud. Elizabeth Hand is one of those writers I tend to read large chunks of aloud—her style always makes me take notice. But I don’t always analyze how she does what she does, so thinking about those kinds of things while I was rereading the stories in Saffron and Brimstone: Strange Stories (M Press, 2006; all quotations taken from this text) was both interesting and more difficult than I thought. Warning: spoilers to follow.

When I read, I generally read for either (a) work or (b) pleasure. I analyze so much of the reading I do for work that when I read for pleasure I try consciously not to analyze too much; I will, however, be prompted by particularly fine writing to start reading it aloud. Elizabeth Hand is one of those writers I tend to read large chunks of aloud—her style always makes me take notice. But I don’t always analyze how she does what she does, so thinking about those kinds of things while I was rereading the stories in Saffron and Brimstone: Strange Stories (M Press, 2006; all quotations taken from this text) was both interesting and more difficult than I thought. Warning: spoilers to follow.

“Cleopatra Brimstone,” the first story of the collection, is, for me, a prototypical Elizabeth Hand story—set concretely in a realistic setting but that reality is slowly (inevitably, really) intruded, heightened, broadened by the weird, by the unknown and the unknowable. The story builds to its inevitable end, but Hand drops breadcrumbs throughout the story so that by the end we know there’s no other way the story can end but this way. I paid attention, for example, to how clearly Hand uses subtle repetition as foreshadowing. The repetition of the phrase “Try to get away” comes full circle for Jane. First, her rapist uses it, signifying her powerlessness. When Jane uses the phrase on the men she turns into butterflies, she’s renouncing that powerlessness—now she is the one in control, the one who transforms. But then, at the very end, when David uses that phrase, Jane returns to this sense of powerlessness where “she struggled fruitlessly” (61) against him. The repetition of the phrase “eat you alive” (or its variants) has a similar effect, especially since David uses it twice (and Jane once). Another example of repetition is the last man Jane transforms, Tom Raybourne, who reminds her of David (a “repetition” of David)—and indeed after Tom’s transformation is when David enters her apartment.

The idea of predator and prey (and the struggle of the hunter) works along with those repetitions to build the ending. We watch Jane get stronger and stronger over the course of the story—she first takes back control of her life but going to London, and then further by changing her appearance so dramatically and then luring men to bed where she transforms them through sex. But her strength feels reckless, almost unfocused (why is she doing what she’s doing?), and in the end we see that her sense of strength was not as great as David’s. To go back to foreshadowing for a minute, I was impressed with how Hand constructed David’s increasing aggression over the course of the story, even though he’s not onstage that often, and it’s all in the one scene which begins with verbal bullying (“Who says it’s you I’m worried about” [50]) and ends with more physical bullying (the “vicious pressure” [53] he uses when he presses his heel down on her toes). In the end, the reader is both surprised and unsurprised at David’s appearance in her apartment. The ending is a disturbing choice, as it resolves nothing clearly in the story. I always feel I have to offer something more concrete in my story endings, but I think I’m too heavy-handed, afraid of being so subtle that the reader won’t “get it.” The beauty of how Hand delivers the ending here (and in the other stories) is that knowing what the ending means (or even what the ending is) is not as important as the trip—with its beauty and dread—you’ve just been on.

I also found fascinating Hand’s authorial choice in “Cleopatra Brimstone” to never let the reader inside any of the characters’ heads. What is Jane’s real motivation for her actions? What is David’s? What Hand does so well is to record details—we understand that Jane is trying to transform herself, to regain the carefully constructed control she only thought she had prior to the rape, but only by what she does and says and feels physically, not by what she thinks. The risk, of course, is that readers might not engage with the story because they feel cut off from the characters. I’ve often thought my own characters were too distant and thus the story couldn’t quite connect with its reader, but Hand shows that connection can be made without revealing characters’ interiors by presenting a precise description of that action and dialogue.

Hand’s descriptions in this story fell into two categories: first, lists of details; and, second, butterfly imagery. The detail lists are something that Hand uses in every story, part of her style, but these lists never feel heavy or heavy-handed. When Jane acclimates to London, Hand focuses on the smells: “London had an acrid scent: damp ashes, the softer underlying fetor of rot that oozed from ancient bricks and stone buildings, the thick vegetative smell of the canal, sharpened with urine and spilled beer” (11). Here, where London is so much more sharply evoked than if she’d relied just on visual imagery, is a good reminder to use other sensory imagery when writing description. I’m partial to detail lists myself, but sometimes it’s hard to know the right moment to stop or the means by which using such lists would be the most effective. In The Reader’s Manifesto, one of B.R. Myers’ complaints against “pretentious literary writing” is its use of lists as description, which often are just strings of “lazy, inexpressive adjectives” (as he says when he eviscerates Annie Proulx). But I’d argue against him in the case of Hand’s work, as there’s certainly nothing lazy or inexpressive about her word choices. But Myers does make me think more carefully about my own writing—that if I’m going to list, I’d better make it something more potent.

Hand’s butterfly imagery I thought was subtler, but it does bind the story together. At the beginning of the story Hand uses that imagery more concretely: “Her first three years at Argus passed in a bright-winged blur with her butterflies” (5). Most of the time, the butterfly imagery is used either in clinical terms (which can be applied to the story) or in terms of Jane’s action. When Jane reads the display sign for the Cleopatra Brimstone butterfly—“…the brimstone is a harbinger of spring, often emerging from its winter hibernation under dead leaves” (15)—the reader is prepared for Jane’s transformation: she has been in hibernation and will now be emerge as something altogether different. Why else take Cleopatra Brimstone as her nom de guerre? (And I do think she’s fighting a war, even though it’s not entirely clear—perhaps not even to Jane herself—who she’s fighting against.) The description of David’s assault on Jane also invokes butterflies—“her antennae busting out like flame from her brow and wings exploding everywhere around her as she struggled fruitlessly” (61), just like the butterflies in the killing jars (her bedroom itself, filled with “the bitter odor of ethyl alcohol” coming off of David, becomes a killing jar).

What makes these stories so effective to me is Hand’s style since the plots themselves tend to be rather quiet in this collection. The emphasis is largely on a single character and a singular issue—the death of Carrie’s friend in “Pavane for a Prince of the Air,” the weird reconnection to humanity for Ivy in “The Least Trumps,” the narrator’s vision of Rimbaud in “Wonderwall,” or Calypso’s artistic devouring of her married lover in “Calypso in Berlin.” The world’s not in peril (even in “Kronia” and “Echo” the world’s dangers are far removed from the character), there’s nothing explosive happening, but those singular characters embody the whole world. I’ve often felt that my own writing is too quiet, but I see in Hand’s work that a quiet examination of a character can actually bring about an explosive revelation.